Articles

Breathing Buddha: Science and Dzogchen on the Interconnectedness of Breath

Each breath contains sextillions of oxygen atoms, and over thousands of years, these atoms have been redistributed countless times through respiration, photosynthesis, and chemical cycles. In effect, with every inhalation, we are physically connected to all life that has ever existed, and every exhalation contributes to the ongoing circulation of life itself. each inhalation is a literal communion with every being who ever lived. Science confirms what spiritual teachings have intuited for millennia: we are not separate from the lives and breaths of those who came before us. In Tonglen practice, inhalation is an act of embracing suffering; exhalation is offering relief and compassion. Now consider: with each inhalation, we are literally drawing in the same atoms that once filled Buddha’s lungs. And every exhale returns those atoms, now imbued with our intention, back into the world.

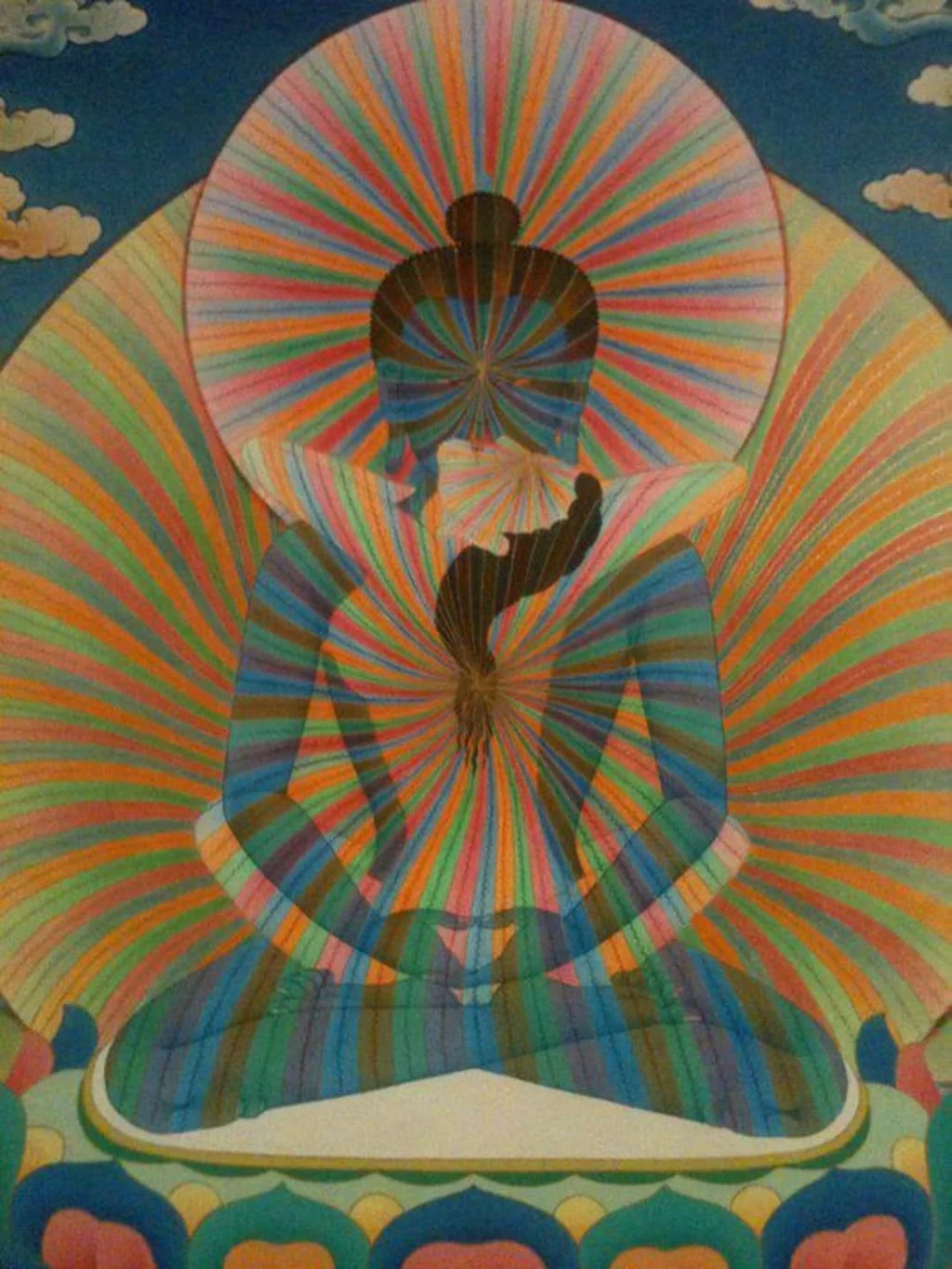

The Two Accumulations: Unifying Awareness and Compassion in Dzogpachenpo

Because awareness is empty, it is free to appear. Because it is luminous, appearance is never inert or dead. Thoughts, emotions, sensations, and perceptions arise as the dynamic energy of awareness itself. They are not intrusions into awareness, nor are they obstacles to it. They are its natural display. This is what is meant by spontaneous presence.

Refuge Without Flight: Āśraya, Skyabs su ’Chi, and Resting in the Groundless Ground

āśraya is not a place one enters. It is that without which entering itself would be unintelligible. It is not a shelter constructed against threat, but the very condition by which anything stands, appears, or is sustained at all.

When one says āśraye, therefore, one is not grammatically saying “I flee.” One is saying something closer to “I take my stand,” “I repose,” “I rely,” “I rest upon.”

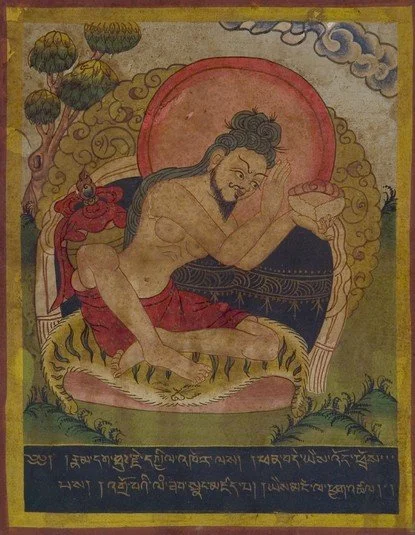

Sahaja, Mahāmudrā, and the Great Perfection

Dzogchen is neither reducible to Sahajayāna nor separable from it. Mahāmudrā is neither a duplicate nor a simple intermediary. All three arise from a shared contemplative insight, yet each becomes articulated through a distinct doctrinal body, linguistic register, and pedagogical architecture, shaped by historical circumstance, soteriological intent and revelatory impetus.

Garbha (Nyingpo): Embryo, Womb, and the Precious Secret Space

The threefold meaning of garbha as embryo, womb, and precious concealed space does not describe three different things. It articulates three inseparable dimensions of a single reality.

As embryo, garbha speaks to the lived unfolding of recognition, to the way confidence and continuity mature over time without implying any lack in the base. As womb, it reveals the all-encompassing expanse in which all phenomena arise, dissolving the boundary between samsara and nirvana. As precious heart, it emphasises subtlety, intimacy, and the need for careful, experiential safeguarding.

Su-kha, Duḥ-kha, and the Space of Being

The earliest experience of sukha/duḥkha was not psychological: it was ecological. The world either opened or closed; life either flowed or was constrained. The metaphor was not metaphorical. It was environmental fact: good space (su-kha) versus bad space (duḥ-kha).

To this day, traces of that archaic spatial worldview survive in how the mind interprets ease and struggle. When obstacles recede, when the environment feels navigable, the body relaxes into sukha. When conditions tighten, the felt-sense contracts into duḥkha.

This is remarkably close to Dzogchen:

Rigpa = unobstructed openness, the view as vast as the sky

Avidyā = constriction, tightening, narrowing of the view.

Zangthal: The Meaning of Transparent Immediacy as Unimpeded Openness

zang carries meanings that include pure, clean, open, free from stain, and devoid of solid obstruction.

thal conveys the sense of completely penetrating, utterly exhausted of limit, to the end, through and through, or fully extended.

When combined, the term evokes something like “utterly open”, “completely unimpeded”, or “transparently penetrated to the depths”. What is important to recognise here is that the term does not simply denote clarity as a superficial brightness or a sensory vividness. It signifies openness to the point of limitlessness.

Bliss, Clarity, and Non-Conceptuality in Longchenpa’s Hermeneutics: The Three Nyams

The three classical nyams of bliss, clarity, and non-conceptuality are neither simple psychological states nor subtle meditative absorptions. They represent patterned outcomes of rlung dynamics when the karmically-conditioned configuration of the winds temporarily relaxes. Their appearance is a sign that the practitioner’s system has entered a distinct form of resonance with the view, but this resonance is unstable. The nyams, by their very nature, cannot remain. For seasoned practitioners, the question is not how to evoke or measure these states, but how to situate them within a non-dual epistemology capable of distinguishing between conditioned luminosity and unconditioned presence.

The Twenty-One Semdzins of the Dzogchen Tradition

Although often categorised as preliminaries for trekchö, the twenty-one semdzins serve multiple pedagogical functions. They are appropriate for novices, since they generate immediate experiences of clarity. Yet they are equally relevant for advanced practitioners, who use them to re-stabilise recognition when subtle obscurations arise.

The Single Taste of Essence, Nature, and Dynamic Energy

The teachings of the Great Perfection reveal reality as the sole thiglé in which all appearances, all knowing, and all energies are inseparably present in a single taste of primordial purity and spontaneous presence. Although this wholeness is beyond conceptual limits, Dzogchen masters have provided complementary triads to guide practitioners toward recognition.

When the Base is not Grasped, It is Seen to be Groundlessness

The most beautiful and liberating insight of Dzogchen is not that the ground is “nonconceptual,” but that:

liberation is immediate,

awareness is innately free,

nothing needs to be added or removed,

saṁsāra and nirvāṇa are not two,

and the ground is not an object.

Mipam summarises:

“When the ground is not grasped,

it is seen to be groundlessness.

This is the ground of Dzogchen.”

Clarifying the All-Ground (Kunzhi) and the Base (Gzhi)

For Dzogchen practitioners, especially those who are serious about cultivating the view (lta ba), understanding these distinctions is more than a matter of intellectual curiosity: Clarifying the difference between kunzhi and gzhi helps prevent the reification of a ground, the subtle clinging to an absolute foundation. It is also a way to appreciate the astonishing precision of the Dzogchen teachings.

The Twenty-One Tārās of Jigme Lingpa and the Twenty-One Tārās of Atīśa: A Dzogchen-Oriented Comparison

For practitioners on the Dzogchen path, the decision to use the Atīśa system or the Jigme Lingpa–Longchen Nyingthik cycle depends on purpose and timing.

The Atīśa system offers clarity, structure, and accessibility, making it ideal for communal rites, devotional strengthening, and practical ritual needs.

The Jigme Lingpa tradition offers greater contemplative depth, integrating subtle-body yogas with the luminous immediacy of rigpa.

Dzogchen and the “Three Natures”: An Inquiry into the Yogācāra Connections of the Great Perfection

Both Dzogchen and Yogācāra speak, in different languages, about a dimension of experience that is already complete, unmanufactured, and inherently free.

The Value of Ngöndro in Dzogchen

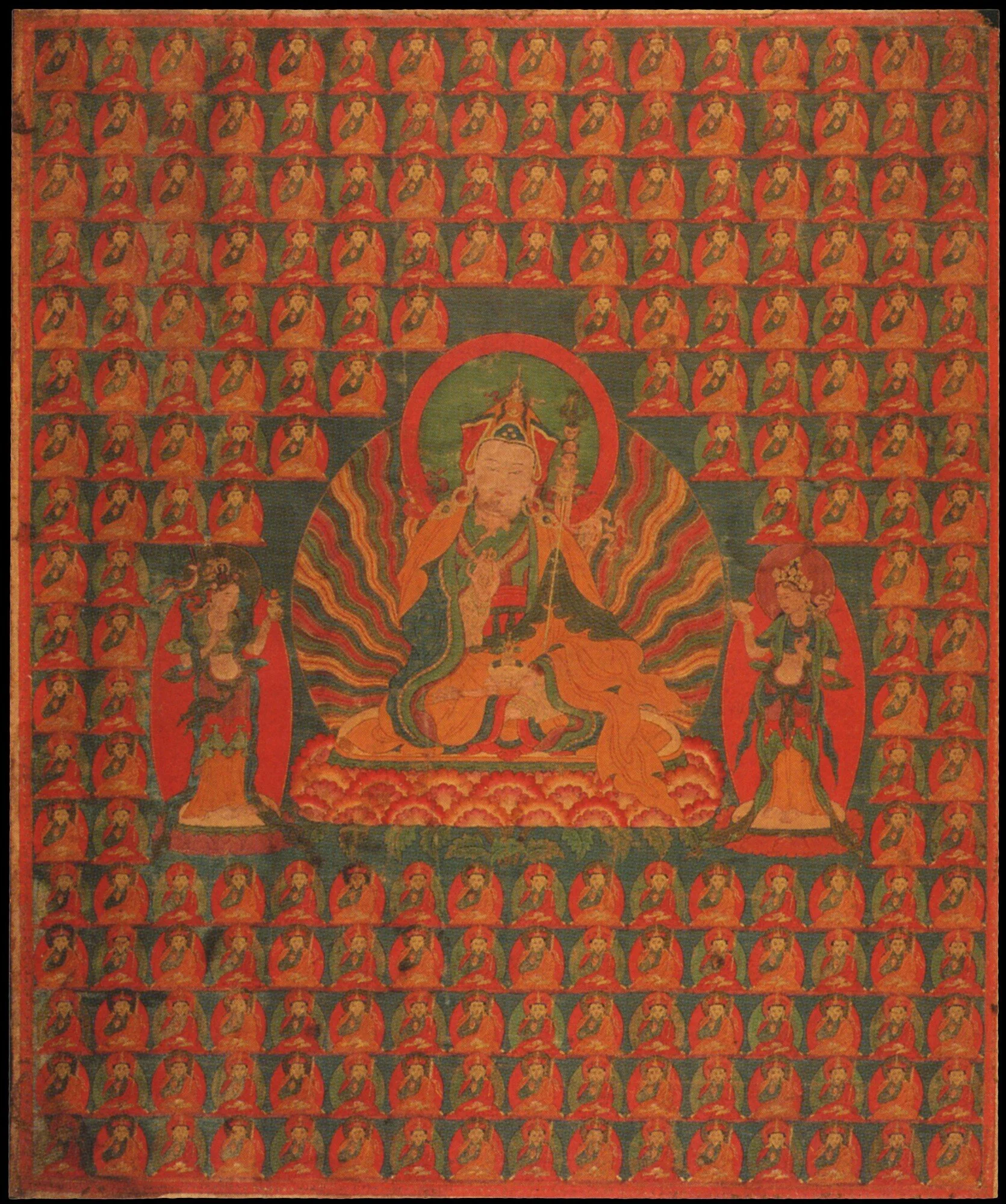

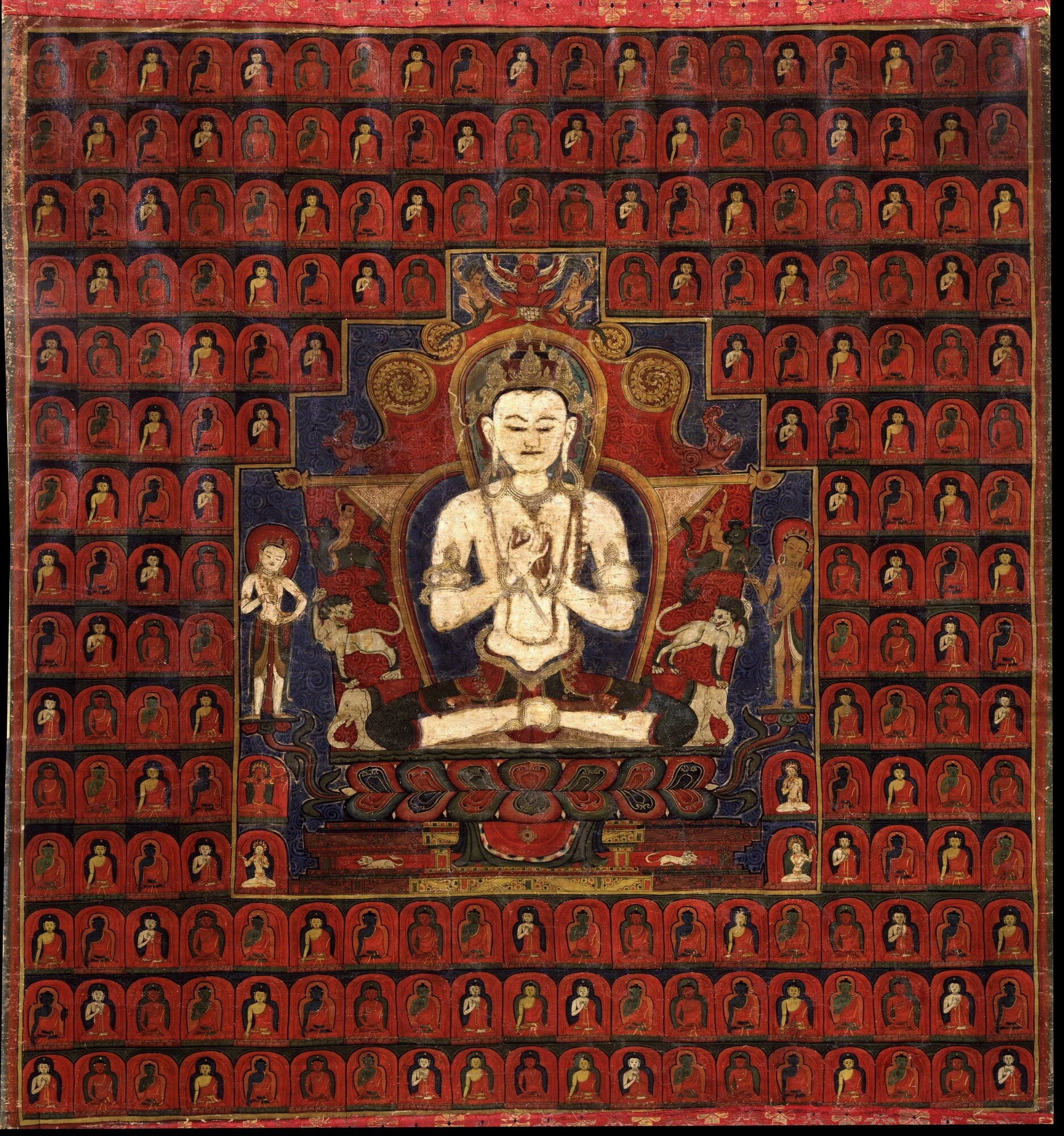

For centuries, masters of the Great Perfection have debated whether ngöndro — the “foundational practices” of refuge through prostrations, bodhicitta, Vajrasattva purification, maṇḍala offering and guru yoga — is required for entry into Atiyoga.

The issue is not merely academic. It touches the core question of spiritual maturity, readiness, and the delicate relationship between direct introduction and the actual capacity to sustain the experience of rigpa.

The “Magical Net” in Dzogchen

In Mahāyoga, the “Magical Net” (sgyu ’phrul dru ba) denotes a structured maṇḍala of deities, energies, and symbols designed to embody enlightened qualities and guide the practitioner through ritual transformation.

In Dzogchen, the term shifts to describe the self-arising, luminous display of the Ground itself: appearances unfolding spontaneously, inseparable from the awareness that perceives them, beyond structured form or deity arrangement.

Thoughts on Dependent Origination

The early Buddhist concern is not to describe the interdependence of mountains, rivers, organisms, and societies, but to identify the internal dynamics that bind sentient beings to the cycle of birth and death.

Mipam’s Vision of the Basis

Mipam describes the relationship between emptiness (stong pa nyid), luminosity (’od gsal), and awareness (rig pa) through the metaphor of mutual illumination. This teaching is both philosophically rich and experientially essential for Dzogchen practitioners. Rather than treating these three as separate elements that must be woven together through intellectual reasoning, Mipam presents them as three inseparable aspects of the single primordial nature of mind.

Candrakīrti on “own-being” or inherent essence

What truly “belongs” (ātmīya) to something is that which is unproduced, non-artificial (akṛtrima).